By Jim Moodie; photos by Laura Arsiè

originally published in Cottage Life July/August 2000

It’s a clear, still evening in late August, and Pam Wedd is standing beside a leaky canoe that’s been packed full of ice and beer. A fit, thoughtful woman who builds exquisite wooden canoes at her Bearwood Canoe Company shop on the Seguin River near Parry Sound, Wedd would ordinarily be horrified to see a canoe–any canoe–put to such an undignified use. The canoe-cooler, however, doesn’t offend her. The boat’s fiberglass, it has lousy lines, and, hey, didn’t she tell you that nothing will last as long as cedar? She helps herself to a Superior Lager and joins the fun.

About 20 other people–including Jane Liddell, with whom Wedd shares a cozy, weathered, slightly ramshackle cabin down the road–are here as well, reviving what used to be an annual tradition among the dozen or so cottages that cling to this same strip of rugged Lake Superior shore. A corn roast. Chris Rous, an affable, mop-topped public school principal from Sault Ste. Marie, is one of the few present who actually remembers the last one. Consequently, he’s the host. To anyone who asks what inspired him to convert a canoe into a cooler, he has a practical response. “I figure with all the holes in this thing, it will just drain itself!” Coloured lights that Rous inherited from a used car lot festoon the surrounding trees, while at the water’s edge his three sons are collect driftwood for a bonfire.

After dinner Wedd and Liddell excuse themselves, promising to return later for one of the ‘adult hot chocolates’ Rous is planning to whip up as a nightcap. Within minutes, they are alone on the water, gliding in Liddell’s beloved, green Chestnut Pal through a vast, private universe where the soft plop of their paddles is the only sound, and the only light a tiny beacon winking at Whitefish Point, some 30 kilometres distant on the American shoreline. The two paddle leisurely, while also keeping an eye out for rocks. Even 30 metres from shore a surprising variety of boulders–erratics left here by glaciers, and huge, nubbly conglomerates–looms eerily, if beautifully, near the surface.

After dinner Wedd and Liddell excuse themselves, promising to return later for one of the ‘adult hot chocolates’ Rous is planning to whip up as a nightcap. Within minutes, they are alone on the water, gliding in Liddell’s beloved, green Chestnut Pal through a vast, private universe where the soft plop of their paddles is the only sound, and the only light a tiny beacon winking at Whitefish Point, some 30 kilometres distant on the American shoreline. The two paddle leisurely, while also keeping an eye out for rocks. Even 30 metres from shore a surprising variety of boulders–erratics left here by glaciers, and huge, nubbly conglomerates–looms eerily, if beautifully, near the surface.

Lulled by the movement of the canoe, Cedar, their two-year-old golden retriever, snoozes peacefully beneath the centre thwart. As soon as the paddlers take a break to stretch their legs, he rears his tufty head, thinking (wishfully) that the pause in human activity might be his long-awaited cue to happily leap overboard for a swim.

“Cede,” Wedd says, firmly. A name that doubles as a command. The retriever slumps back down onto his blue mat.

Silence, again, prevails. There is not another craft on the horizon. A sliver of sun still peeks over Pancake Point. “This is what we love so much about Pancake,” Liddell says, expressive blue eyes glinting in the orange light. “It’s sociable. But you can still go places and be alone.”

‘Pancake’ is, for Wedd and Liddell, a sort of catch-all endearment. Strictly speaking, it’s the name of the bay they are paddling on, the broad arc of blue that their cottage overlooks. It’s also their name for the cottage itself–a place they still can’t quite believe they acquired as easily as they did 10 years ago, and one which, in keeping with local parlance, they should really be calling their ‘camp.’ Often by ‘Pancake’ the two mean to include the other cottagers in their row, some of whom are old friends, others people they are likely to see more and more of as the years, and reactivated yearly corn roasts, go by.

At a moment like this, ‘Pancake’ means all of this and more. It means friends and privacy and incredible good luck. It means sitting in a canoe and feeling small and blessed while balancing lightly upon the largest lake surface in the world.

At a moment like this, ‘Pancake’ means all of this and more. It means friends and privacy and incredible good luck. It means sitting in a canoe and feeling small and blessed while balancing lightly upon the largest lake surface in the world.

Although it’s as flat as one now, Pancake Bay was not named for its physical resemblance to a flapjack. Local lore has it that the voyageurs, running short on supplies that they would replenish in the Sault, would habitually pause on the sand beach lining the bay’s north shore to fry up what remained of their staples: namely, flour and salt. Anyone who has driven across Ontario on Highway 17 will have passed within sight of this beach, possibly stopping to picnic or camp in the provincial park that hugs the three-kilometre crescent of sand.

Neither the park nor the highway intrude too much on Wedd and Liddell’s cottage experience. Errant beach balls do regularly wash up on their shoreline; earlier this day, the two found an inflatable killer whale. But they don’t see or hear too many people. “It’s nice being on the boulder side of the bay,” says Wedd. Boat traffic is scarce, and as for those semis that chug up and down the Trans-Canada at just about any hour, Wedd shrugs: “When we get waves, you don’t hear them anyway.”

That would be most of the time. While more sheltered than some of the other bays scalloping Superior’s coast, Pancake still takes a beating. Asked about the curious absence of docks in the cottage community, Wedd laughs. “Docks? It’s hard enough keeping a water line in.” Wedd and Liddell don’t bother with either. They wade their canoes and kayaks into the lake; in place of running water, they have a two-seater outhouse, a solar shower bag they string from a tree, and plenty of pails. The two have electricity, but keep oil lamps on hand. An average Superior storm will not only knock out power in an instant, but can easily uproot trees, rip shingles off roofs, and deposit entirely new collections of boulders on cottagers’ shorelines. Occasionally, the storm gods can be more generous, as they were for Wedd and Liddell this past spring when a chunk of sand was removed from the mouth of the Pancake River and plunked in front of their place. “I’ve been coming here 10 years, and this is the first time we’ve had a beach,” says Wedd, still marvelling at their good fortune.

For Wedd and Liddell, who both grew up in southwestern Ontario, this raw, unpredictable power is a large part of Pancake’s appeal. Even though they make their home now in rural Muskoka, surrounded by water and trees, each August, Thanksgiving, and March Break they heap a trailer full of kayaks, mountain bikes and tools (if it’s March: snowshoes, cross-country skis and tools) and begin the seven-hour trek north. “There’s something about Superior that’s very different from Georgian Bay and central Ontario cottage lakes,” muses Wedd. “The ocean has that same sort of feel–there’s a real power to it that’s compelling, but also quite scary.”

If the two need a reminder of how scary Superior can be, they need only glance, as they often do, at the Whitefish Point light. Even from the porch of their cabin this beacon is visible; while paddling it tends to take on a more immediate if somewhat less comforting cast. The Edmund Fitzgerald, when it plunged off the radar screen and into the popular consciousness one stormy night in 1975, was just shy of this landmark. As Gordon Lightfoot memorably intones: “The searches all say they’d have made Whitefish Bay, if they’d put fifteen more miles behind her.”

As darkness gathers, Wedd and Liddell gently turn the Chestnut Pal–a boat some 713 feet shorter than the Fitzgerald–back towards the cottage, carefully following the boulder-strewn shore until they reach their tiny beach.

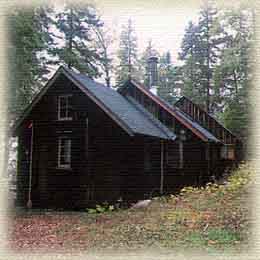

On one wall of the cottage–in what Wedd and Liddell call the “main cabin,” to differentiate it from the bedroom and “bunkhouse” that were tacked on a few years after this original dwelling was built in 1948–the pair has hung a large Ojibwe drawing, with the word ‘Respect’ written below it in black letters. It is one of the very few adornments they have added to a setting that has otherwise changed very little in 50 years. Old potato chip tins bearing forgotten brand names still clutter one shelf; bright Fiestaware, dating from the period when the dishes were radioactive. “We hid those ones away for a while, but we missed the colours,” says Liddell. Nearly everything the two inherited when they took over the cottage, they have kept.

They have made a few changes. While reshingling the roof they decided to install a skylight, and added a gable to accommodate a small sleeping loft. Wedd and Liddell did all this work themselves. (“I’m real good at ripping things apart. Pam’s the finishing carpenter,” says Liddell.) They also introduced a “new” cookstove–a vintage Climax, built by the Guelph Stove Company–and an airtight woodstove to take the place of the propane heater they were bequeathed. They have left the walls as they found them–rudimentary, uninsulated. Roughsawn pine planks, some more than half a metre wide, lend the interior of the cabin a rustic, yellow tint; on the outside, the boards wear their original covering of dark creosote, plus battens, to keep the weather out. At least, that’s the theory. When Wedd and Liddell visit Pancake in March, they often have snow blowing in through the cracks.

They have made a few changes. While reshingling the roof they decided to install a skylight, and added a gable to accommodate a small sleeping loft. Wedd and Liddell did all this work themselves. (“I’m real good at ripping things apart. Pam’s the finishing carpenter,” says Liddell.) They also introduced a “new” cookstove–a vintage Climax, built by the Guelph Stove Company–and an airtight woodstove to take the place of the propane heater they were bequeathed. They have left the walls as they found them–rudimentary, uninsulated. Roughsawn pine planks, some more than half a metre wide, lend the interior of the cabin a rustic, yellow tint; on the outside, the boards wear their original covering of dark creosote, plus battens, to keep the weather out. At least, that’s the theory. When Wedd and Liddell visit Pancake in March, they often have snow blowing in through the cracks.

That they haven’t done much to alter the character of the original “camp” says a lot about the two friends’ tastes: They like old stuff. For her canoe shop at home, Wedd decided to renovate a listing post-and-beam barn that was on the property, rather than construct a new building. In the hay loft, she now stores 18 classic canoes in various stages of disrepair–these are mostly her own canoes, not customers’–that one day soon, when she finds the time between her paid restoration work and the eight or so new canoes she turns off her mold each winter, she fully intends to fix up.

But the most compelling reason for preserving the cottage, as it was, has to do with gratitude. And yes, with respect.

But the most compelling reason for preserving the cottage, as it was, has to do with gratitude. And yes, with respect.

“Getting this place was a gift from the goddesses, the gods,” says Liddell. “We got it because we were extremely lucky, and because the people who had it before us were very, very generous.”

Not that the cottage came, exactly, on a platter. Nor did the transaction occur overnight. It was a full 20 years ago now that Liddell first set her eyes on ‘Pancake.’ After a stint as a community youth worker for the White Dog First Nation in northwestern Ontario, she ended up in Sault Ste. Marie, working with special needs children in the public schools. There, she met Chris Rous. “I’d been looking for a place to escape to on the weekends and holidays, and I already had an attraction to Superior, just from driving back and forth on 17,” she says. A visit to Rous’ Pancake Bay cottage not only got her hooked on the area’s elemental beauty; it offered up an opportunity for future, private visits in the form of a rarely visited cabin at the far end of the cottage road.

Learning the owners’ names and address from Rous, Liddell quickly sent off a letter in which she volunteered to maintain the cottage in return for using the place on occasion herself. The Jokis, an elderly couple from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, did not require an interview. “They sent the key in the mail,” says Liddell, amazed by their trust.

Learning the owners’ names and address from Rous, Liddell quickly sent off a letter in which she volunteered to maintain the cottage in return for using the place on occasion herself. The Jokis, an elderly couple from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, did not require an interview. “They sent the key in the mail,” says Liddell, amazed by their trust.

Liddell met the Jokis just once, shortly before they passed away. She drove to Michigan to do so. “They were a very kind, gentle couple,” she says, adding, “They loved the area too. Otherwise, they would have sold it much earlier.” When the two died in 1989, Michael, their son, offered Liddell and Wedd the property for a remarkably low sum. He even volunteered to hold the mortgage and not charge interest on the payments. The cottage Liddell had come to think of as a place she was fortunate to even have access to, was suddenly theirs for keeps.

One thing of her own that Liddell introduced during the period when she was still caretaker, and which remains a fixture to this day, is the Chestnut Pal.

It is not the only boat at Pancake. Both Wedd and Liddell are accomplished kayakers (Wedd has worked as a kayaking guide and instructor, through the White Squall Paddling Centre near Nobel, Ont.) and each summer the two lug a pair of sleek, practical sea kayaks along with them to the cottage. More rarely, Wedd might also bring up one of her own, flawlessly crafted canoes. But the Pal is the true cottage boat, the one that belongs here, the one that never leaves.

It is also the canoe that Wedd based her own hull design on. As a youngster attending Tapawingo, a YWCA camp on Georgian Bay, Wedd learned to paddle in a Chestnut Pal. As a tripping guide, and eventual director of Tapawingo, she would continue to use and maintain the camp’s fleet of Pals. This offering of the legendary and now-defunct Chestnut Canoe Company–a model that was part of the company’s “Canvas Pleasure” series intended for camp and cottage use–went beyond being a “pal” for Wedd. It became a true intimate, a life-long friend. It’s a relationship obvious in the way she now paddles Liddell’s canoe–her friend’s ‘friend’–but also in the language she’ll unconsciously use to describe it, as when she remarks, “I’ve known Jane’s canoe since 1988.”

Sentimental attachments aside, the Pal also struck Wedd on a purely utilitarian level as being the finest multi-purpose canoe that had yet to be designed. Canoe guru Bill Mason, of course, touted the Chestnut Prospector, a deeper, roomier cousin of the Pal with a more pronounced rocker. But Wedd points out that Mason also owned, and regularly used, a Pal. Indeed, in many scenes in his films, it is the more manageable Pal, and not the Prospector, that is on display.

In canoe building lingo, Wedd “took the lines off” the Pal for her first mold. She then modified the shape slightly, putting her own touch on the archetype. The Bearwood canoes–the Seguin 16,’ Shadow 15’, and Northern Lights (lightweight versions of the Seguin and Shadow)–are a bit deeper than the Pal, have a little less tumblehome, and turn up more prettily in the ends. But each retains the same versatility that made the Pal such a logical choice for cottagers. A Bearwood canoe is capacious enough to carry some gear and a dog, or a couple of children, and still manage waves, but is also, with its fine lines and responsive handling, wonderfully suited to solo paddling.

The Bearwood Canoe Company was officially launched in 1989, a few months before Wedd and Liddell acquired their cottage. Wedd came up with the name, she says, after watching a succession of large black ursines systematically trash what had, prior to canoe building, been one of her main obsessions: beehives.

Wedd no longer keeps bees. Canoe building takes up too much of her time now, although she still, between coats of paint, we presume, manages to play for two hockey teams throughout the winter, her busiest canoe building season. If you want to know what position she plays, all you have to do is look at the posters decorating her workshop. On one wall, there’s Felix Potvin, sporting his big pads and a maple leaf-emblazoned mask. On another: goalie Manon Rheaume, in her Tampa Bay Lightning sweater.

The woman who has been perhaps the greatest inspiration to Wedd, however, peers less famously from a black-and-white newspaper photo tacked near the shop entrance. May Minto, now 83, toiled in virtual obscurity for the Minto Canoe Company of Minden, Ontario, for three decades. She was the company’s principal builder, continuing in this role even after her brother sold the business to a new owner in the 1970s. Minto, whom Wedd has visited a couple of times, built 25 wood-canvas canoes a year on average until she retired in 1983. Wedd is not the first woman to build wood-canvas canoes, and she will be the first to tell you as much. She is, however, the only female canoe builder in Canada to operate her own company.

The name Bearwood, according to Wedd, was also intended as a play on words. If so, it must be loaded with irony, because the canoe that goes out the door of Wedd’s shop is decidedly short on ‘bare wood.’ Of all the wooden canoes on the market, Wedd’s are among the most meticulously finished craft available, glowing with the liberal and smooth coats of varnish that have been painstakingly applied to every inch of wood. The wood itself, while not exotic in variety–Wedd uses the traditional cedar for ribs and planking, and locally available cherry or ash for thwarts and decks–is also unique in appearance. Wedd employs a technique known as ‘book match’ planking, meaning the grain of one cedar plank mirrors another at the seam. This is accomplished by milling all of the planking stock for one canoe from a single, 5.5 metre chunk of vertical-grain red cedar.

The name Bearwood, according to Wedd, was also intended as a play on words. If so, it must be loaded with irony, because the canoe that goes out the door of Wedd’s shop is decidedly short on ‘bare wood.’ Of all the wooden canoes on the market, Wedd’s are among the most meticulously finished craft available, glowing with the liberal and smooth coats of varnish that have been painstakingly applied to every inch of wood. The wood itself, while not exotic in variety–Wedd uses the traditional cedar for ribs and planking, and locally available cherry or ash for thwarts and decks–is also unique in appearance. Wedd employs a technique known as ‘book match’ planking, meaning the grain of one cedar plank mirrors another at the seam. This is accomplished by milling all of the planking stock for one canoe from a single, 5.5 metre chunk of vertical-grain red cedar.

Not that Wedd thinks much about such matters while she’s ensconced at the cottage; at least, she tries not to. That a phone has yet to make an appearance at Pancake certainly helps. On a typical evening (corn roasts, both Wedd and Liddell will remind you, are not typical events at Pancake), or in the late afternoon after a bike ride with Cedar, or a paddle, or a swim, the two will sit on the screened-in porch overlooking the bay and watch the waves roll in.

For Liddell, it’s a break from her current job as a high school teacher and guidance counsellor, an opportunity to drink in the same view she’s now known for 20 years.

Wedd thinks of these moments as a way to escape the more worrisome aspects of her work–whether the next batch of red cedar is going to arrive on time; whether she’ll make enough money this month to keep apprentice Johanna Neuteboom (a young woman she values not only for practical help, but as a friend) on the payroll–and to daydream about the future projects she’d love to attempt. She’d like to add a 17-foot tripping canoe to her line, possibly build a new solo mold, and she’s always wanted to build wooden rowboats. At one time, Wedd would bring canoe seats that needed caning, and accomplish some of her work while sitting on the porch. Now she has someone else–apprentice Edie Hentcy–who does the caning for her. Which is fine with her–if she’s going to do work at the cottage, let it at least be work on the cottage.

Most of the time, Wedd and Liddell visit Pancake on their own, but at least once a year they invite guests. For the past several years Thanksgiving has been the time for entertaining. Neuteboom has been to Pancake twice, and Hentcy made her first visit at Thanksgiving two years ago. Wedd’s mom has visited several times, and some of Liddell’s fellow teachers have also made the trip. Turkey is no longer done in the Climax cookstove, after coming out rather raw one year. But as long as the weather’s nice, they will try to continue a tradition of eating the Thanksgiving meal on the beach.

While they have a beach.

And weather permitting–beach or not–you can be sure of this: At some point during the festivities, before or after the meal, it doesn’t really matter, Wedd and Liddell will be sneaking away for a mandatory, private spin in the green Chestnut Pal.